Hardware First, Market Later?

The Dual-Use Timing Trap

“Everyone says, ‘Go commercial first.’ But what if your market isn’t ready — and your product still matters?”

If you’re building hardware that’s regulated, safety-critical, or just plain weird (in the best way), the usual startup playbook tries to route you through a door that doesn’t exist yet. Get quick commercial traction, people say. Then go after defense.

For a lot of dual-use teams, that advice isn’t just unhelpful — it’s directionally wrong.

The Reality

The “go commercial first” playbook works in software because products are lightweight, easily pivoted, and instantly distributed. You can test, iterate, and redirect with minimal cost. Hardware isn’t like that.

For dual-use builders, the reality is messier:

Timelines aren’t symmetric. It can take years to validate materials, certify systems, or field-test in mission environments. Trying to force a “fast commercial cycle” into that cadence is like mixing oil and water.

Specs don’t bend easily. A composite pressure housing designed for 6,000 meters isn’t going to find a weekend hobbyist market. You can’t just relax the requirements and call it a beachhead.

Regulation and qualification matter. Whether it’s MIL-STD, FAA certification, or NIJ ballistic standards, you can’t cut corners for the sake of traction.

We’ve seen this dynamic play out close to home with Regent Craft in Rhode Island. They began with an electric seaglider for commercial transit — a textbook “go commercial first” strategy. Along the way, they built a scaled-down prototype as an engineering step to validate performance for the larger craft. That prototype wasn’t even meant to be a product. But now the DoD is interested in it directly, as an autonomous platform in its own right.

That’s the paradox: the defense market didn’t line up with the polished commercial vision. It latched onto the byproduct of the development cycle. You can’t roadmap your way into that kind of pull — you just have to build honestly and let the right users see the value.

We’ve found the same tension in our own process validation. Take out-of-autoclave (OOA) composites. Commercial buyers push for cheaper, faster methods — OOA promises exactly that. Defense, meanwhile, is locked into autoclave because it’s validated, safe, and predictable. On paper, those markets look misaligned.

Yet, if we can prove OOA performs on par with autoclave, it’s not just a commercial advantage. It becomes a bridge: defense gains a faster, more scalable process without compromising reliability.

The reality of dual-use is this: commercial-first thinking is dangerous when it drags you into irrelevant beachheads — but powerful when it forces validation of something defense will eventually demand.

The Problem

Dual-use hardware founders are often steered toward a commercial-first strategy — and recent real-world evidence shows how dangerously misaligned that advice can be.

1. Funding Surges, but Hype Can Outpace Reality

As Business Insider reports, “venture capital investment in defense-related companies rose 33% year-over-year to $31 billion in 2024,” with multiple headline-grabbing raises (Saronic Technologies, Epirus, Shield AI). Yet many VCs worry “hype may be exceeding reality,” warning of a growing wave of underperforming “zombie startups.” (Business Insider)

This is exactly how founders get trapped: the market rewards flashy raises and press cycles, but it punishes slower, harder engineering work. If your milestones are optimized for fundraising optics, you’re incentivized to chase easy commercial wins, regardless of whether they actually validate your tech. That’s how companies end up with sky-high valuations but shallow capability, stuck in a cycle where the gap between story and delivery only widens.

2. University Accelerators — Enthusiasm Meets Tension

The Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) recently launched a 12-week accelerator to help university-borne startups engage with DoD. It’s modeled on Y Combinator and reflects the growing enthusiasm for dual-use innovation. But even insiders are skeptical. As one put it bluntly: “Too many DoD problems are defense problems, not dual-use problems.” (Business Insider)

That’s the heart of the tension. A program might encourage startups to chase dual-use optics early, framing their value around commercial traction or broader applicability, when in reality their best shot at impact is solving a defense-specific challenge. The result? Teams spend precious cycles proving the wrong things, trying to make their tech “fit” into a market that doesn’t need it, instead of leaning into the mission-critical problems that actually justify their existence.

3. Struggling Between Markets: Procurement Is a Valley of Death

While venture dollars are flooding in and accelerators open doors, structural realities remain. An Inside Defense piece notes that 40 percent of companies formerly in the defense industrial base have shifted focus to commercial markets, simply “because it is just too difficult to work with the department.” (National Defense Magazine)

This illustrates the dual-use valley of death. Caught between long, bureaucratic defense procurement cycles and commercial markets that don’t value, or won’t pay for, their highest-performance work, many companies get stranded. Instead of doubling down on validation, they pivot to “easier” commercial opportunities that never scale. In the process, they dilute focus, burn capital, and lose the very technical edge that could have made them indispensable.

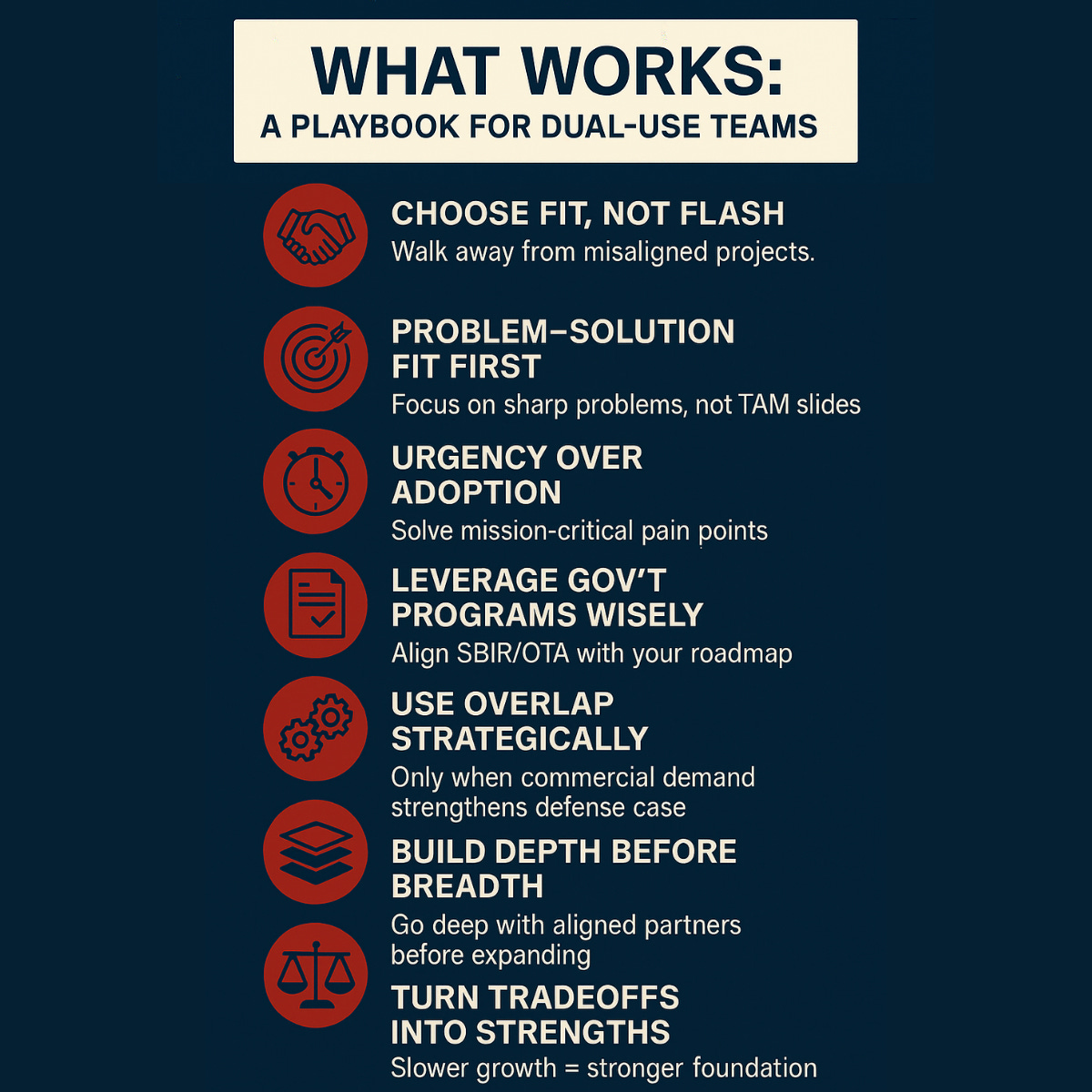

What Works (for teams like ours)

If “go commercial first” is the trap, then what actually works?

For dual-use builders, the playbook looks different. It’s slower on the surface, but deeper in impact.

Here’s what we’ve found:

1. Choose early partners for fit, not flash.

A mission-aligned pilot with a smaller check often beats the wrong big customer. We’ve learned that choosing partners who care about performance validation gives us sharper feedback, tighter requirements, and more realistic roadmaps. A flashy logo that doesn’t actually need what you’re building only pulls you sideways.

We’ve had conversations where we’ve said: “Yes, we could build that, but we might not be the right people to.” For example, a foiling windsurfer company approached us because of our experience with high-performance foils. Technically, we could have delivered. But that project wouldn’t have advanced the portfolio we’re trying to build, it wasn’t a meaningful challenge, and it wouldn’t have pushed our capabilities forward. The harder choice was to walk away.

2. Optimize for problem–solution fit over market-size optics.

In early conversations, it’s tempting to frame your market in terms of TAM and slide-deck billions. But those numbers rarely matter when you’re validating hard tech. What matters is: can your first customers clearly articulate why they need you, and what happens if they don’t get it?

We nearly chased a “beachhead” market that looked attractive but had no tolerance for the performance tradeoffs our tech refused to make. It would’ve generated nice screenshots, and the wrong roadmap. Walking away cost us short-term growth, but it preserved the alignment that mattered.

3. Frame around urgency and mission, not mass adoption.

In software, adoption is everything. In dual-use hardware, urgency is everything. The strongest pull we’ve felt hasn’t come from hypothetical market studies, it’s come from teams who literally can’t do their mission without the performance we’re trying to unlock. That urgency is worth more than a hundred lukewarm commercial trials.

When we started work on composite pressure housings for subsea systems, the commercial market for shallow-water housings wasn’t compelling. But the urgency from teams pushing into 6,000-meter depths was immediate and mission-critical. That urgency drove our roadmap, and forced us to engineer at a level no shallow-water customer ever would.

4. Leverage government programs without losing focus.

SBIRs, OTAs, and pilot contracts can be a lifeline, they fund development, create test data, and expose you to real requirements. But they’re not just “free money.” They’re only useful if they line up with your core roadmap.

Sometimes that means turning down a shiny commercial contract with more immediate upside for a smaller government R&D effort that could be short-lived. It’s a hard tradeoff, but when the government work sharpens your process or proves your capability, it pays off far more in the long run.

5. Use commercial overlap strategically.

Here’s the nuance: sometimes commercial demand does accelerate defense adoption. Our validation of out-of-autoclave (OOA) processing is a prime case. Commercial markets want speed and cost savings, defense trusts autoclave because it’s validated. On paper, those markets look misaligned. But by proving OOA meets or exceeds autoclave performance, we’re not chasing a beachhead, we’re building a bridge. The overlap works only when it strengthens the defense case, not distracts from it.

We’ve seen the same dynamic with Regent. Their commercial push for electric seagliders led them to build a small-scale prototype, which the DoD now sees as valuable in its own right. That wasn’t planned as a dual-use product, but because it solved a real engineering problem, defense adoption followed.

6. Build depth before breadth.

It’s easy to chase a broad set of customers early, but the reality is that hardware timelines and capital constraints don’t allow for “land and expand” in the same way as SaaS. We’ve benefitted more from going deep with a few aligned partners, iterating closely, and building credibility, instead of spreading thin across half-interested prospects.

Our early work with Nautilus is a good example. Rather than chasing multiple scattered projects, we chose to go deep with one partner, refining processes around multifunctional composites. That depth gave us a level of technical integration and trust that would’ve been impossible if we’d split our focus.

7. Translate tradeoffs into advantage.

Every dual-use team faces a tradeoff: slower top-line growth in exchange for deeper product knowledge. Instead of hiding it, make it an advantage. A slower early pace often means fewer wrong turns, less rework, and a stronger position when scaling becomes possible.

For us, that meant accepting that early revenue charts looked less impressive than they could have. But behind the scenes, we were building playbooks for pressure housings, foils, and OOA validation that will carry us through the next decade. It’s not flashy, but it’s durable, and durability is what wins in defense.

The Argument

“Hardware-first” isn’t bad business, it’s honest sequencing. You’re playing a longer game where urgency lives in need, not in slide-deck TAM.

And here’s the nuance: you don’t have to ignore commercial entirely. You just have to know when it’s a detour, and when it’s a forcing function. If commercial pressure helps you validate a process or capability defense will care about, take it. If it just pads your metrics for the next raise, skip it.

Sometimes, as Regent’s path shows, the value defense sees isn’t even the thing you thought you were building for them, it’s the prototype, the side-product, the byproduct of solving real engineering problems. That’s why sequencing matters more than optics.

You don’t need to prove a market exists. You need to prove you can serve it, reliably, repeatedly, at the required performance.

Nail that, and you’ll discover something funny about timing: when the market does show up, it wants the thing you already built the right way.

Shop Talk — From Last Week

Prompt from last week: What’s one big decision you made before your market fully existed — and how did it play out?

Here’s what you shared:

Anon founder, autonomous systems:

“We started building long-range UUVs before the Navy formally had a program for them. For years it looked premature, but when the RFPs finally dropped, we were the only ones with data. Painful wait, but the bet paid off.”Small defense supplier:

“We launched a new materials process knowing commercial aerospace wasn’t ready to certify it. It forced us to live off tiny defense contracts for two years. Brutal financially — but that early validation made it easier to bring Boeing and Lockheed to the table later.”Dual-use hardware startup:

“We wasted 18 months chasing a consumer market that didn’t exist. When we finally pivoted to defense, we realized the tech was already good enough. The lesson: prove the hard market, don’t chase the easy one.”

These stories echo a common theme: sometimes you’re early, sometimes you’re wrong, but either way — the decision teaches you where to stand when the market catches up.

Shop Talk — For Next Week

Talent risks and bets: what worked, what didn’t, and how are you training or learning on the job?

👉 Have you ever had to prove your value without credentials? How did you do it — and what helped build trust?

Reply here or email me directly — I’ll include a few stories (with credit or anonymously) in next week’s issue.

👀 Liked this post?

Subscribe to get weekly dispatches from the middle miles of dual-use, defense, and manufacturing.

Real tech. Real truths. Delivered straight to your inbox.